Bio

What did you do in the war, Daddy?

My father, Christopher (always known as Kip), spent five years as a prisoner of war between 1940 and 1945. After marrying my mother, Jean, in 1939, he was sent to France almost immediately, and captured within a year. As the years went by and he was moved from one prison camp to another, he probably felt that he would never get out alive. After the war ended, life was for living and not looking back – certainly not dwelling on a miserable time in his life. Like others of his generation, he never liked to talk about the war.

But once, and only once, he told me about his war experiences. I was probably 12 years old. We were in our swimming trunks, sitting at a table on the grass by the side of the swimming pool at the Tanglin Club in Singapore. It was late afternoon, and the sun was starting to go down, as families made their way home after a day’s frollicking.

“I escaped from prison twice,” was my father’s opening statement.

“What,” I stammered. “You escaped? How? For how long? How were you captured?” I could barely believe what I was hearing. Here was my father, whom I loved deeply and had so much fun with (he introduced me to the joys of cricket and trad jazz), suddenly opening up after years of saying nothing.

Over the next hour or so – I can’t remember how long, but I do remember my mouth was agape the whole time – my father related his time in prison and how he escaped. He told how he came up with the ideas of how to escape. One of the plans involved building a false wall underneath a prison hut. The huts were raised up off the ground to stop prisoners digging tunnels but were supported on all four sides by brick walls. The guards would regularly check underneath with their torches. My father thought that if the prisoners built a false wall at a slight and growing angle from the side square wall, the guards would not notice. As the gap between the real and false walls increased, that would offer a big enough space at the end to create the opening for a tunnel without being detected. Which is exactly what they did.

Then he told me of the time that, mid-escape, he was in the middle of a tunnel when everyone had to stay still because there was a warning of nearby guards. The air was not being pushed through by the movement of those in the tunnel. My father thought he was going to suffocate. “I gasped for air when we finally did make it out,” he said. “I have never been so grateful for oxygen.”

That time, he was captured after two days on the run. He was regarded as a troublesome prisoner, and sent to Colditz, considered to be inescapable by the Germans. (They were wrong.) My father decided his escaping days were finished. He passed the rest of the war sleeping as much as he could. That is how he got his nickname.

He never spoke again about this war exploits and his brave escapes. He died in 1980. How I wish I could have recorded that conversation and told his story. But I have never forgotten that evening by the swimming pool in Singapore.

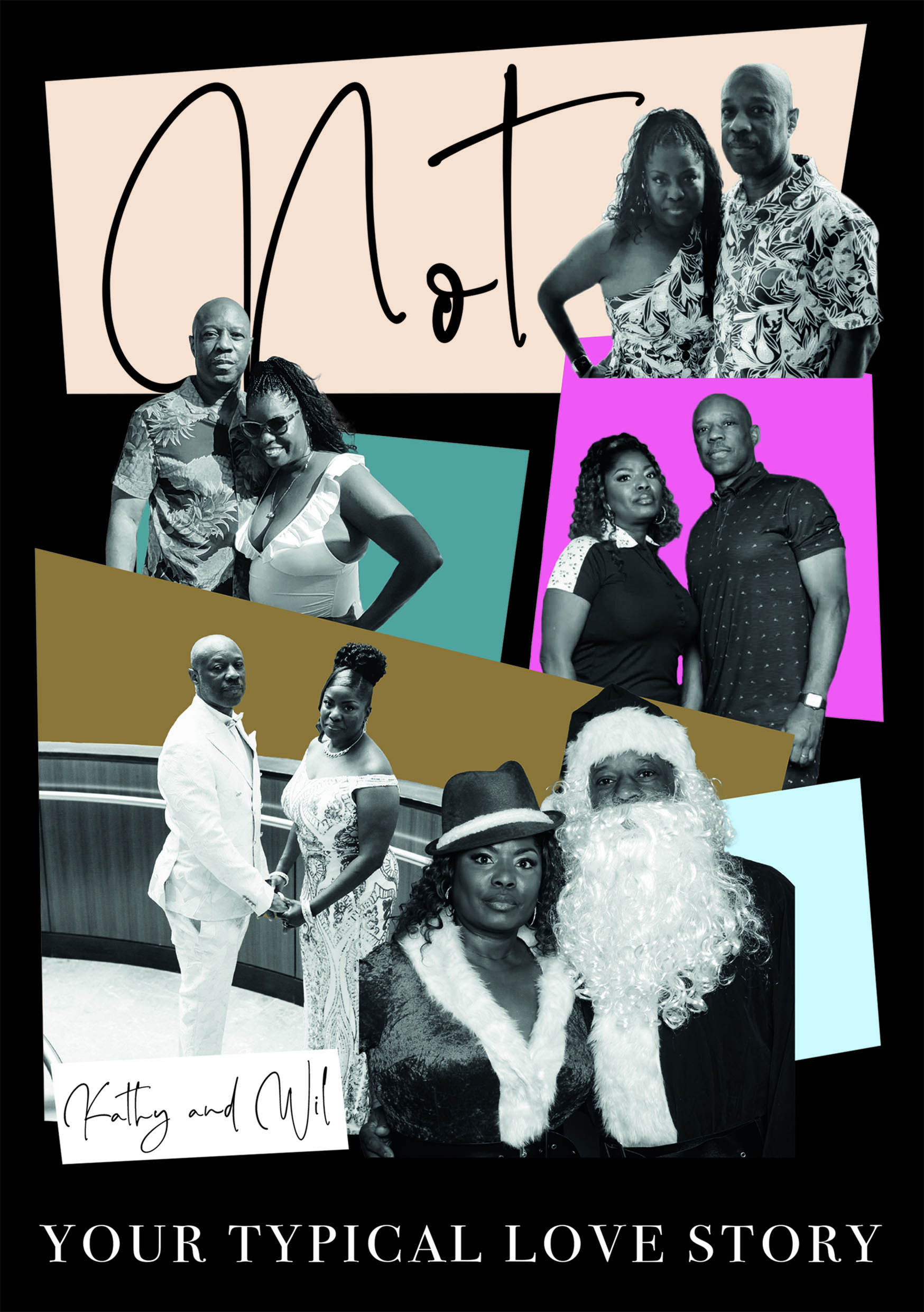

[Caption] Father and son, by the side of a cricket field

.jpg)

.webp)